What do a pair of recycled plastic sneakers, a bulk dispenser in supermarkets, a neighborhood compost and the new repairability indicator that has just arrived on cell phones and new lawnmowers have in common?

All of these inventions (more or less) that have emerged in the 21st century correspond to the logic of the circular economy, a concept that comes not from the field of economics but from that of sustainable development, and which aims to free itself from the "extract-transform-use-discard" model.

It is based on the idea that by taking inspiration from natural ecosystems, the biological cycles of renewal of nutrients and natural balances will be respected, and in particular the capacity of organisms to absorb and transform the waste of some into energy or resources for others. Adopted by industrialists and public actors, this idea is becoming a major catalyst of the ecological transition.

A truncated approach to the environmental crisis

The circular economy offers a conceptual framework that helps decision-makers to understand two of the major environmental challenges of today, namely the waste crisis and the depletion of mineral and fossil resources - a political, economic and environmental issue.

The risk of focusing on these two challenges alone is to miss other less visible issues, such as global warming, the loss of biodiversity or the toxicological effects of our activities on humans and ecosystems. These are all issues that require more conceptualization and exploration if we are to overcome the environmental crisis we are facing.

This focus also reduces the complexity of anthropogenic systems to their production and disposal, without questioning their use, maintenance, transportation or their usefulness to society and individuals.

Even for sectors where the majority of environmental impacts are associated with resource extraction and waste disposal, such as packaging, the most effective solutions to limit the sector's impact, such as reuse, require a complete rethinking of this object, its uses and the interactions between actors in the sector.

Fake good ideas in the name of "circularity

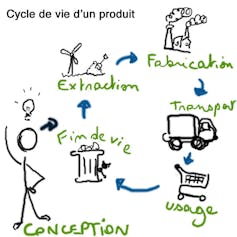

Life cycle thinking allows for an evaluation of products according to several environmental criteria at once, which go beyond the simple manufacturing stage. In particular, it integrates the actors who have contributed to its design, its use and those who will have to deal with it at the end of its life. It is a tool that puts some environmental complexity back into the analysis of anthropic systems.

Life cycle of a product.

Wikimedia

The Ecodesign Directive is the direct application of life cycle thinking to energy-related products. In particular, it has led to significant energy savings, but also to improved longevity of certain objects such as vacuum cleaners.

Applying this framework to some of the solutions promoted in the circular economy highlights an environmental and societal balance sheet that is not always as positive as hoped.

The case of chemical recycling of plastics

Let's take the chemical recycling of plastics. Today, plastics are rarely recycled because of their multiplicity. Behind plastics there is actually a variety of materials with different properties, which makes them difficult to separate in the waste treatment infrastructure.

The chemical industry, together with the waste and plastics industry, is currently promoting chemical recycling as an end-of-life treatment solution.

Unlike today's technologies that rely on mechanical tools such as centrifugation, flotation, shredding and extrusion to recover material, chemical recycling promises to revert to primary chemical elements to resynthesize any plastic from any waste containing it, using a series of chemical reactions such as pyrolysis.

Environmental analyses based on life cycle thinking have revealed that this technology is less efficient than plastic incineration. It only becomes interesting when the plastic streams are relatively homogeneous.

In this case, mechanical recycling is also able to produce a quality material with a lower environmental impact.

The recycled plastic sneaker

Let's go back to our pair of Adidas Ocean Plastic sneakers, made from large pieces of plastic collected on beaches (and not in the oceans, as the name suggests).

The challenge is not to reuse the plastics collected on our coasts but to avoid finding bottles, cups and fishing nets washed up in the oceans.

Adidas' ambition to reduce the environmental impact of its products by using its own plastics rather than virgin raw materials distracts stakeholders from the real challenge of plastics leakage into the aquatic environment.

In addition, the logistics involved in the massification of plastic flows and the manufacture of shoes can be more emissive than burning or recycling plastics locally. Beyond the 8,000 kilometers travelled in total by truck to collect, densify and send to the production site, incinerating plastic has less impact on global warming.

From a life cycle perspective for textiles, it appears that the environmental issues are related to the frequency of maintenance (washing, drying...) and their life expectancy.

On this point, Adidas misses the boat by proposing light colored shoes, very dirty, which will disperse microplastics in the natural environment with each wash. There is also the question of the durability of the pair and the aging of this new material over time.

Complex thinking and the urgency to act

The urgency of the environmental crisis requires a profound transformation of our industrial activities and our daily lives. Proposing solutions that are more resource efficient and less wasteful is an integral part of the response to climate change.

However, the risk of going too fast is to promote ideas that are relevant in the short term but harmful in the long term. In the field of the circular economy, Dutch researchers have highlighted the waste/resource paradox.

By wanting to find an outlet for waste at all costs, industrial systems are developed to give it a market value. While by rethinking the initial production model, they could simply never see the light of day.

This desire to make the filthy waste disappear at all costs also leads to the development of technologies with very low environmental performance, which consume a lot of energy or produce emissions that are harmful to health and the environment.

The holistic approach to environmental issues must also be applied to the circular economy so that each option considered is assessed in terms of its consequences on natural and human systems.

Lucie Domingo, Associate Professor in eco-design, UniLaSalle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.